Meeting me where I am—quickly, please

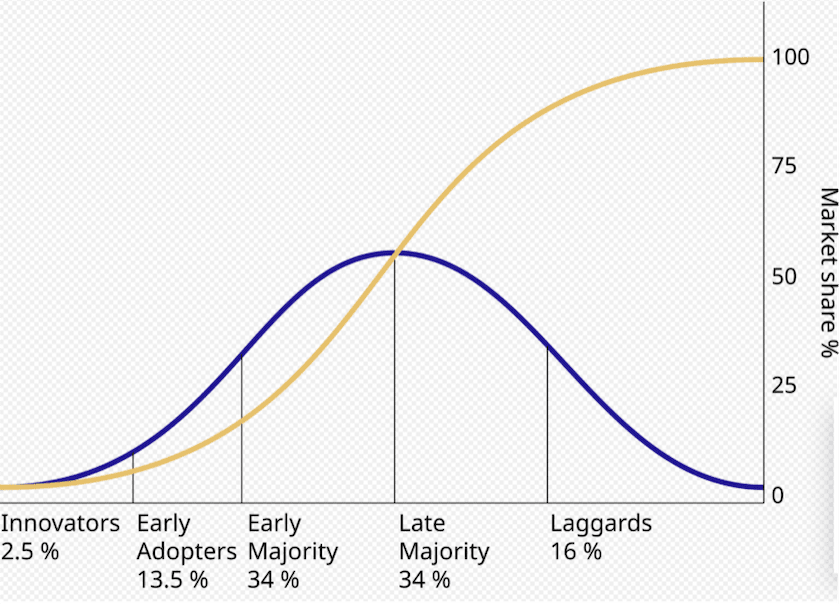

AI holds real potential for improving quality and efficiency in healthcare. But to turn that potential into reality, it helps to consider the diffusion of innovation curve—a 1962 framework describing how new ideas spread through groups—created by communication theorist and sociologist, Everett Rogers.

I’d also suggest thinking about something else: me. What makes me—a clinician, a team member—willing to try something new? To embrace new tools? What builds my confidence, earns my trust, and makes it easier to move forward? Understanding these dynamics is just as important as the technology itself. That’s how innovation takes root—and grows.

The diffusion curve has an unlikely origin: corn. More specifically, the spread of new hybrid corn seeds among independent farmers in Iowa. The first to embrace the new seeds (which were more resistant to disease) was a small group (2.5%) described as innovators: They read about the seeds, liked the idea, and gave them a try. They were followed by the early adopters (13.5%), then the early majority (34%). Eventually, the late majority (34%) and laggards (16%) came around.

When I learned about the diffusion curve in a college course, I desperately wanted to be an innovator. Innovators are creative and cool. But in my heart, I knew where I really belong: I am most at home in the early majority.

And that’s okay! Each of us along this curve plays an important role.

I’m interested in new ideas, tools, and technologies—like AI—but I’m not someone who develops them, and I’m never the first person to try them either. Most people in any category on the diffusion curve are nervously watching those in the category to the left. They’re nervous because they’re not excited. Why? They don’t necessarily want to do something new, but they’re watching from the sidelines, waiting to jump in, because they don’t want to miss out on something big and important.

So, the early majority types are keeping an eye on the early adopters, but they think the innovators aren’t worth worrying about. The same is true for the late majority: They can be swayed by the early majority, but do not surrender to what the early adopters do. As for the laggards? They only give in once the late majority comes along.

When innovations have real advantages over “business as usual” (like the hybrid corn seed in Iowa), they eventually spread through the market (the rising curve on the figure). And when they are nothing less than wonderful (like ambient AI for note generation during office visits), the spread can occur over just a few years. But the fact is, spread cannot happen fast enough, and organizations that can accelerate the diffusion curve will deliver better and more efficient care—and have happier employees.

Happier, that is, once they’ve made the transition, and adopted the innovation. And the fact is, most people aren’t thrilled by the reality of learning something new and making it routine.

This seems like an appropriate moment to confess something. I began talking about how great ambient AI was for doctors in February 2024, after Kaiser Permanente described its early experience with the technology. But I only started using it myself a year later, after a small group of clinicians where I practice had a very successful pilot.

Even though I knew that almost all clinicians using ambient AI for documentation loved it, I was still nervous. I set aside an hour to watch the multiple online training videos, but within five minutes I had learned enough to get started. Truth be told, I never finished the rest. I’m sure there are skills I could still pick up to get more out of the tools. But at that point, I just wanted to dive in. And I haven’t gone back.

Even just knowing the basics, I realized something fantastic was happening by 8:45 a.m., when I was seeing my second patient. First, I wasn’t writing anything down or typing—I was simply looking at her. For a second I worried she might be thinking, “Stop staring at me. You’re making me nervous.”

But the bigger revelation was that I wasn’t anxious about forgetting anything. I’ve always prided myself on being reliable, but too often I found myself obsessing, “I said I was going to do three things—what was that third?” And nothing felt worse than forgetting something I promised.

With that second patient, I realized I didn’t need to fear forgetting those promises anymore. The things that I said I would do—they were all right there at the end of the note generated within a few seconds after the visit.

I hadn’t even realized how much the “fear of forgetting” had been weighing on me my entire career until that weight was lifted from my shoulders. The relief made me happy. I actually started smiling. I remember turning away from my patient to the computer—not because I needed anything from it, but because I didn’t want the patient to wonder why I was grinning!

The version of ambient AI I use isn’t perfect. For example, it tends to skip over social issues like the death of a spouse, or concern about a child caught in the middle of their parents’ divorce. I still need to type those things in myself. But there’s a reason so many physicians are saying it’s helping them remember the joy of medicine.

That mix of imperfections and unexpected joy is exactly why adoption matters—and why leaders can play such a powerful role in helping it spread.

So, how can the leaders of healthcare organizations help their employees make this kind of leap, faster, and scale AI adoption in months rather than years? My answer is simple (and predictable): Build social capital. Cultivate connections among colleagues, and encourage the spread of information across those connections.

On the diffusion curve, slower adopters do best when they have contact with faster adopters who can help them make the leap. Research consistently shows that earlier adopters have broader and more diverse social networks than late adopters. These broader networks accelerate their exposure to new ideas and prepare them to embrace those ideas faster. This means that organizations can speed the spread of new ideas by “bridging” connections across their organizations.

Recently, a fellow baby boomer told me the ecstasy he felt when he realized he could deposit checks via his smartphone instead of going to the bank. If you didn’t live through that transition, you can’t appreciate how liberating it was. I told him I felt something like that when I saw my second patient with ambient AI.

Clinicians who are coming along will probably never know the relief I felt that day. But they’ll have their own breakthrough moments. I can’t wait to see what they are. And I hope we can use social capital to make them happen faster.

By Rogers Everett - Based on Rogers, E. (1962) Diffusion of innovations. Free Press, London, NY, USA., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18525407